|

| |

| |

| |

Encounters at Sea

I. Recognition

IT was the wild western coast of Ceram, the stronghold once of slave-hunters and pirates. Between a sky dark with stormy cloud-rack and a dull grey sea palely writhing with slow trails of foam, the forbidding rock rose black. Puny the ship lay under the lowering steep. The passengers sat silent as if the darkness that overcast the sea and the sky, that seemed to be exhaled by those sombre heights, lay black and heavy on their own hearts too.

Down the beach, a narrow strip of pale sands clinging to the base of the rocks, there moved a long file of coolies heavily burdened and stooping under the load. It seemed to go on for ever, beginningless and endless, that long file, still gliding on between the rocks and the ship, dimly discerned in the grey of mist and sea-vapour. The faces of those stooping figures remained invisible, hidden between raised arms and down-hanging load. Each like every other, all in that identical attitude of strained bearing and stooping, they came gliding on, naked and dark, as if out of the dark rock, soundless, almost immaterial, a train of phantoms breathed forth out of hidden depths.

What thing was it that held them so deeply bowed down, and that, when the dangling grapnel had caught it up from the beach and lowered it down into the hold, fell so heavily as to cause the ship to sink still deeper and deeper under the load?

The merchant from the distant harbour town, who distrustfully counted the bearers, spoke of wood-produce, the sole harvest of this wild island - rattan, and deer's skins and horns, and lumps of speckled-wood, the diseased excrescences on the roots of huge trees in the primeval forest, more valued than the sound stem, since some rich man's whim chose it for the decoration of his palace. And of this too spoke the young army officer with the ghastly cicatrice across his forehead, sent out to crush the rebellion which alien traders had instigated amongst the head-hunting Alfoors of the interior.

But it seemed impossible that the thing which made that train of

| |

| |

phantoms bend down so deeply and the ship herself stagger like an overburdened slave should be but deer's skins and horns and gnarled boles. It could be nothing on which the sun had ever shone. The inscrutable procession bore a thing unbearable, heavy and cold and black as the rock out of which the dark bearers issued. Not on their backs they bore it, but in their hearts. And it was because of this that the seamews, restlessly wheeling about the ship, screamed so loudly and shrilly, with such piercing shrieks. How they cried woe and vengeance with their discordant clamour, to which the echoes made answer complainingly!

Even thus, on this very coast, shrieked in utter need and despair the wretches whom the Ceram pirates assailed. Even thus resounded, from the steep of the rock and out of hidden caverns, the lamentation of prisoners haled into the stronghold hard of access, impossible to escape from. There sat the Sea King, like an eagle on a crag, spying into the distance for sails. Wings spread, the trading prao fled. Pale faces, distorted with fear, turned toward the reef where the pirates' skiff, quick as the darting snake, lay in wait. The rowers, dry-throated, panting, strained to breaking their hurrying arms and bodies spasmodically pulling, as they strained away from the fearsome thing from which they could not keep their haggard eyes. The limpid water grew red as, with a leap fiercer than the tiger's upon the wild cow, the Ceram prao seized the trader.

But red into all distances, red with the red of blood and the red of fire, grew the waves and the hills when he came who was stronger than that strong one, he who slew tens of thousands for the hundreds slain by the Alfoor - the conqueror from the West, who struck not as the Alfoor struck, with hands merely in which there was the weight of wood and stone and the edge of metal for a weapon; nay, he struck with his thought also, and with the elements which by the power of his thought he had changed into his weapons, with earth transformed into a thunderous flame, with air pressed into a death-hurling sling. He spoiled the spoiler, he hunted the hunter, he slew the slayer, he left none alive but slaves. Then the thing began which was to endure into a future beyond sight, which endures even at this present day; endures in secret, creeping in tortuous darknesses, in the forests of the wild interior, in the black western firths clamorous with the shrieks of seagulls, in the hearts of the isle-folk. Then the thing began under which

| |

| |

they stooped rancorously, even as those burdened coolies stooped, who hid their faces as they came down the narrow strip of beach toward the Westerners' ship - the ship of the strong-of-thought, in which they have the seething sea-waves for their rowers, and call the lightning to their mast-heads for their messenger - as they came carrying on their bent backs in tribute to the conqueror the growth of the soil once their own.

The gnarled logs and the trusses of rattan, the deer's skins and antlers - how ill the load of it all hid that other burden which they bore, the black weight so unbearably heavy that even the strong ship sank under it like an overburdened slave!

The ship's passengers, the Westerners, the masters of all those bearers of burdens, they felt the heaviness of it on their own hearts.

In a different way each felt the pain dimly felt by all. For in each heart it grew to be a thing by itself, indivisibly one with its own innermost pain, pain suffered, pain inflicted, pain that was named sorrow, pain that was named sin, pain named with whatever other name the confusing words of men may find for it.

As a sick serpent, writhing, raises its head out of its crevice under the hunter's probing spear-thrust, so, stabbed, the ancient pain writhed up out of darkest heart's fold; and an inexorable voice commanded: ‘Suffer yet more!’

The seagulls made plaintive answer.

The wandering screams were so loud, so long in lamentation, that it was a while before a listener of finer ear than the others discerned among the crying voices of the birds the voice of a woman crying. He hearkened, dismayed. But that piteous voice suddenly fell silent again. And it was only the gulls that were heard still shrieking, as if still hunted onward, wheeling about the ship.

But when the officer with the terrible cicatrice mustered his men, he heard from them how a young woman, a girl, hardly more than a child, whom they pointed out to him cowering away trembling, in a corner of the after deck, had all but been haled away by two Alfoors who had posed as her kinsmen, but who had been denounced to the captain as slave-hunters, preying upon women and young boys whom they abducted in their fast-sailing ships to the Eastern islands for the service of cruel masters.

| |

| |

At the tale, one of the passengers said it was impossible to think there could be slaves there where the Netherlands maintained law and order; and another rejoiced in the salvation of the girl, and her trust in the ruling race, that had been so well justified. And it almost seemed as if the dark shadow fallen from the steep of the gloomy island vanished out of brightening eyes; as if the heaviness which the stooping phantom train of coolies had laid on thought were sliding off, and that ancient pain sank into slumber again, when the officer, turning his courageous marked face in going, exclaimed that, within a few weeks, life and freedom would be as safe in Ceram as they are in Holland.

But then the one who, alone, had heard the shriek of the hunted girl asked: ‘Where in this world are life and freedom safe to-day? Which is the Sanctuary that Greed dare not enter as it pursues Need?’

No one answered.

In deepest dark of the heart the old pain shrank back from the Pursuer's recognized gaze.

| |

II. The something other

Around was the infinite.

But the sheltering ship screened them from it. Her strong hull, her superposed canvas roofs, her manifold fittings were between their feet and the depths, their heads and the heights, their sight and the distances. As, in an unfelt speed, she bore them along between waves and clouds, they sat ensconced in a soft smooth safety as of home, amidst familiar comforts, refined to a luxury that, mingling with their blood like the tropical air, soothed them into a dreamy content.

The silent servants, moving inaudibly on bare feet, had brought to the table, set out in a breezy place on deck, goblets, dim with cold, of golden-brown wine and profusely heaped dishes of fruit, ruddy apples, fresh as when with a soft thud they dropped into the deep dewily shining September grass, apricots flushing between yellow and crimson, full clusters of grapes, transparently white, some with opal-like gleams of faintest brown and pink, others blue almost to blackness, the bloom upon the large perfectly sphered berries intact, figs, purple at the core, melon-slices, brilliantly hued. One of the passengers expressing ad- | |

| |

miration, the captain, carelessly as it seemed, named the various countries in which the ship's purveyor had chosen the pick of the market; and the talk, gliding on in questions and answers, glanced from the dark Spanish wine in the goblets where the ice made a faint fine tinkling against the crystal, to the white marble of the table, the furniture in the smoking-room and the saloon, yesterday's dinner. And countries were named, each for a special produce, selected each for a special quality of softness to the sense - Spain, Italy, Brazil, the jungles of Borneo, Alpine meadows, vineyards of France, the Newfoundland coast, Australian cattle-ranges - till it seemed as if somewhere in the far away, they were lying there, dark and soft in their fleece of forests and undulating harvests, like a herd of gigantic milch-cows, patiently yielding an abundance of sweet food.

A middle-aged man, with an able energetic face, observed: ‘Ah, that is what “civilization” means.’ And the others gravely nodded assent.

A youngster, reddening boyishly, said: ‘The Oriental having proved himself absolutely incapable of achieving this, the Westerners' supremacy over him...’

‘Exactly,’ said the able-faced man decisively.

And the youngster, blushing still more deeply, added: ‘As his teacher and guardian, I meant...’

No one noticed. For there was a sudden cry: ‘A wreck, a wreck! and men on it, signalling!’

Black on the sparkling blue of the sea, a raft tossed, half submerged. Something dark fluttered above the crouching shapes huddled together on it. The captain, frowning, gave an order to the young ship's officer who had come up to him. The ship changed her course, heading for the raft.

‘Three men on it!’

‘Yellow men - Chinese.’

‘They hardly move. All but dying, it would seem.’

As the steamer reached them one of the gaunt, livid-faced shapes made a gesture of drinking. Pails of water were lowered to them and heaped-up baskets of rice.

They flung themselves upon the water, thrusting their heads into it, and gulped with a horrible rattling sound, in convulsive gasps that

| |

| |

shook their angular shoulder-blades and flanks all hollow under the jutting ribs. At last, raising dripping faces with water running out of the mouths, they struck claw-like hands into the rice and bit at their fists, clenched upon the food. The hollow faces were livid under bristling tags of hair burnt rusty-red; the plaits hung down their lean backs matted and filthy, like the tails of sick beasts; there were loathsome whitish blotches on their legs and feet.

At last, glutted, they looked up into the crowd of faces gazing down at them over the railing of the tall ship.

One of the three called out something, in a hurtling jerky language.

A reply came in similar sounds. A sudden gleam lit up the dull faces. The three of them together, they shouted at the man who understood their dialect. They were, they said, men of Hai-Nan, trading along the coast from the gulf of Tongking to Rangoon. The monsoon had seized and disabled their junk. Miles out of their course they had drifted, till they ran upon a reef. There the gale and the breakers battered the junk to pieces, and one of them died. They had tied together boards into a raft, and for three days and three nights rowed and drifted whither the wind tossed them. They had all but gone mad with thirst; was it far to the coast still?

The captain pointed to where, invisible still under the horizon, the summits lay of the Sumatran hill-range.

A boat was lowered, in which there lay oars and a compass.

The Chinamen carried into it a long bundle done up in mats, that had lain carefully fastened to the raft. And the interpreter asked them what most precious possession it might be that, of all their goods, they had solely saved out of the wreck and, in such imminent danger of foundering, carried with them for three days and three nights.

But at the answer they made, he stood as one who does not understand or is unable to believe. And he asked again.

And the bony livid face, bristled about with spikes of reddish-black hair, that looked up into his face, nodded, and said ‘Yes,’ with mouth and eyes. Yes. Yes. And the other man pronounced a few words, and the third a few words also, in a still tone.

Then he who had asked became as a beach that lets the ebb flow off and, utterly empty and wide, bares itself to the tide coming on resplendent and thunderous.

| |

| |

He turned toward the people on the ship and said slowly, and as he spoke his face grew pale and luminous: ‘Their comrade who died in the gale, his body they rescued from the wreck, in order to bury him as the holy law ordains, in the land of his forefathers; that his soul may be at peace in eternity.’

It became very still on the ship. Many eyes were cast down.

But the captain gave a hurried order. Men came running with long poles and thrust off from the ship the vessel of death. It glided away over the waves. Those who stood gazing after it saw it dwindle into a darkly tossing speck upon the blue.

If thoughts could grow visible, a fairer radiance than of resplendent sea-birds' flight would have shone about the dead man and the guardians of his soul, about the will that sought the infinite.

| |

III. Ships dancing

Over the darkling sea, out of the unseen, the subtle fragrance had come floating toward the ship - the fragrance of the tropical eucalyptus, which Malays call the whitewood-tree, Kayoo-pootih. And at dawn the island rose into view, grey as rain and grey as mist, grey with Kayoo-pootih woods. Grey the straight slender stems, grey and straight and slender as streaks of rain on a windless day. Along the steep rock the innumerable frail white trees make a streaky greyness as of continuous rain. And the delicate pale airy foliage hangs like drifts of mist over rain-saturated soil.

The captain pointed at the cloud-like island.

‘That is Booroo, Booroo of the Kayoo-pootih woods. Do you smell the scent on the wind? And see, here the traders are coming with the precious oil!’

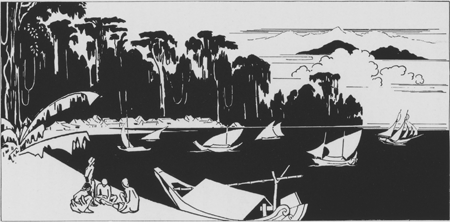

The boats, large and small, were coming on in shoals. Chinese junks were foremost, and Booghi ships, proud of build and bow as seventeenth-century galleys. Orembays of the Moluccas followed, rowed by twenty rowers, outriggers resembling a large water-bird with a young one at either side, and, agile as flying fish, dugouts, darting past and through the press of the other craft.

The passengers were standing by the railing; the traders came clambering on to the deck. Then a giving and taking began that made silver

| |

[pagina t.o. 46]

[p. t.o. 46] | |

Booroo

| |

| |

to gleam in brown palms and brightly green flasks of oil in white hands and yellow.

The beautiful Arab woman by whose side an even more beautiful daughter stood, held out a gold piece toward the important-looking Chinese merchant whom coolies followed carrying heavy cases. The girl with the dusky face, soft as a flower within its setting of diamonds dewily sparkling at her ears and throat, smiled when, as the lid fell back, the spicy scent rose toward her.

A bevy of gaudily dressed women and serving-men were beckoning to the traders, to bring them oil for the harem of the Sultan of Batjan.

There were folk from Ambon aboard - Christians in name, they had not lost the ancient Pagan delight in sweet scents. They came hastening toward the oil, and the women poured drops of it on the lace handkerchiefs in which they wrap their hymn books when, of a Sunday, they go to church to show their fine clothes; and letting it trickle along their fingers they spread it over the glossy ripples and wavelets of their blue-black hair.

Even the white people bought, though somewhat diffidently, on account of that bright green colour which is caused by the copper of the primitive native still.

And still barges, praos, dugouts, kept crowding around the steamer, and still the brown islanders kept carrying cases, crates, and panniers full of oil into the hold.

For in northern lands where the sun shines but palely athwart mist and smoke, where trees stand bare of leafage and fragrance for many months together and limbs stiffen and ache with cold, millions were waiting for the sparkling medicine distilled out of odorous leafage and sunshine.

At close of day the ship from keel to deck was as full of oil as, at the end of a plentiful summer, hives are full of honey. It gave forth fragrance as Booroo does, that for miles around makes sweet the sea air. The railing and the very tackle, for all it was soaked and sated with the pungent smell of the sea, exhaled a breath of Kayoo-pootih.

Well content, the traders had looked at the small rolls of silver coins before they hid them away in a fold of their waist-cloths. They thrust off their praos from the steamer.

But not all the boats headed for the island. A group of the larger

| |

| |

ones remained near, one taking up a place behind another, lying in file as if expectant.

Then a tall Booghi ship, under dark red sails, with a stately motion glided out of the file. And striking up a festive music, with a great sound of bronze gongs, of drums, and of flutes, it swept in a wide circle around the steamer, round and round again. All the other ships followed, rowing and sailing; in the wake of the Booghi ship they swept round and around the steamer, wheeling in wide circles and singing as they went. Each one sang a song of his own - each of these great waterbirds, these stately swans of the sea. Every bird sang in his own notes - with shrilly sweet piping and chirping the lesser; the greater in deeply resonant bursts of sound in powerful bronze voices.

The sun set. The sea was all empurpled. The red sails of the Booghi ship caught the evening breeze and flamed up, transparently resplendent.

All ablaze the beautiful ship sailed, purple over the purple sea, leading the choral dance of the ships.

Round and round the steamer it swept melodiously. The musicians were playing with a will, the rowers kept time with a raising and dipping of oars; merrily sailed the fleet.

As, in happier days, youths and maidens danced singing around the May Queen, desiring not nor envying, rejoicing in her beauty, so the Eastern vessels danced around the Western ship, rejoicing.

The men and women of the West, of the lands where joy is as rare and fleeting as the sunshine, gazed wondering. In the evening glow their faces were red as roses. As the ship was filled full of precious fragrance, their hearts were filled full of gladness.

|

|