|

| |

| |

| |

The Vigil by the Bridge

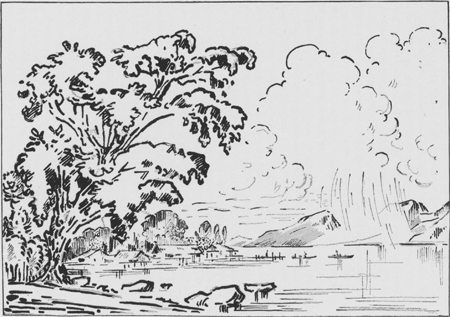

THERE, where the Tjikidool, the tawny turbulent river whose hundred springs are in the heart of the hill country, insuperably severs the steep inland from the coast, there stands the Great Bridge. The masonry of the southern base is cemented into the living rock of the hillside which rises sheer out of the ravine, all green and wooded. The northern head stretches far across the broad boggy margin of the great plain, which in the dry season is a marsh and during the rains a foam-flecked flood. Its mighty central pile, broad-based, rock-like in its enduring strength, is planted in the midst of the dragging swirl of the river. Its twofold triad of boldly swung arches lifts its soaring curves above the surrounding densities of billowing tree-tops.

As it stands there, lofty and huge and broad, the one thing lofty and huge and broad in the wide landscape, the bridge may be seen from distances of miles beyond miles. On the long journey to the plain, up hill and down dale, through the twisting passes of the hill country, beyond which the distant southern peaks shine in a diaphanous glory of blue, this twofold row of slender arches, dominating the surging masses of the forest tree-tops, gladdens the eyes of the hill folk at each sudden turn of the path.

Across all the green breadths of the vast plain, an expanse limitless and level as the sea itself, shining beside the sea, many-tinted green beside many-tinted blue, the people of the plain, from their hundred villages darkly nestling among fruit trees and embowering bamboo groves, see the bridge rising against the distant heights. On the ships hastening from north and east and west to the important harbour city on the coast, the sailors point out the bridge to one another as a landmark. It is the link that binds the hill country to the plain, across the dividing gleam of the Tjikidool.

Like all the rivers of this island world, prone under the vertical cataract of the sun's rays, the Tjikidool is a thing of tides, ebbing and flowing with the ebb and flow of that aerial ocean, the rain. In the ebb tide of the rain, the hot season, it is a brook, a wandering coolness, where

| |

| |

the water wagtails drink, tripping from one gravel bank to another. It has many fords. The village folk walk across, the women hardly gathering up their sarongs. The children, slipping out of the bullock-cart as the team stands still to drink, search out the deeper spots to bathe, calling each other jubilantly to the transparent little pools between the boulders, over which, foaming as it falls, the water comes tumbling, flashing in and out of the shadow of the dripping fern that hangs from the stones.

But when the great floods of the west monsoon season come pouring down, the brook suddenly swells into a swirling torrent; from the great falls under the Batoo Helang, the Rock of the Sparrow-Hawks, where, bursting forth with a thunderous roar out of the black mountain gorge, it leaps headlong into the spacious freedom of the plain, it rushes mud-brown and flecked with yellow streaks of foam, down to the great lake of Telaga Sarodja, the Lotus Water, its final quiescence, whence in five tranquil rivers it flows out into the sea.

For the population of the Tjikidool basin there is at these times no way to the plain but the bridge.

From the beginning of one season of change, therefore, to the end of the other, an unbroken stream of traffic passes over the bridge all day and all night, cool night in which the Oriental loves to travel - a river of human beings crossing the river of waves. Continuous, it flows on, with an even murmur of voices, a soft deep rumour resonant with that ever recurrent O which renders sonorous the speech of so many mountain peoples all over the world - an echo of the bubbling, gurgling sound that comes from under waterfalls and out of torrent-shaken ravines. At regular intervals it is broken in upon by the transitory thudding roar, a sound of the daytime only, of the trains running from the harbour city in the north, whitely resplendent against the blue of the sea, to the many recently begun plantations and industrial concerns in the hill country. Down the middle of the bridge the long file of cars thunderously rushes by in a cloud of dust and smoke, which darkens afar off the mirroring river and the reflections of the little low brown houses crouching together on the bank like native bathers chattering in friendly groups. And on either side of the glittering road of rails, undisturbed by the violent haste and heat, the traffic of the coun- | |

| |

try folk flows evenly on, in long files of pedestrians ever following one another, which, at most, turn aside for a moment when a tinkling bronze bell gives warning of the approach of a bullock-cart, creaking and squeaking slowly along on wheels that are solid disks of tree trunk. Long strings of packhorses, with bulging loads of forest produce, jog past the long strings of people with a rattling clatter of hoofs over the planks, small creatures recognizable sometimes by a slash in the ear as coming from the herds of some chieftain of horse-herds on the wild southeastern islands. As, impatient for the inn on the farther side and a chat with market folk, taking their rest over a meal of rice served up on a shred

of banana-leaf and a bowl of steaming leaf-coffee, the driver eggs them on with a hoarse cry from the depth of his parched throat, they break into a trot that makes the long planking of the bridge to rattle from end to end.

Coming in the early morning and returning in the afternoon, multitudes of children pass over the bridge on their way to and from the school which has been opened since the building of the bridge. The shaggy-headed boys, half in and half out of their gay-coloured badju, show each other their tops or, securely imprisoned in a small tube of bamboo, a cricket caught by night with a decoy light set amongst a heap of stones, which they tease with blades of grass to make it fight. The little girls, their hair oiled and combed smoothly, as shiny as a mirror, and a flower stuck into the comical little knot at the back of the head, walk with eyes demurely east down, carrying their slates and reading-books on the hip, as they see mother do with their baby brother.

Hesitatingly, and avoiding the stream of the young and alert, there move along - not a day passes without many of them coming - those who seek the new hospital, some shading their eyes with their hands from the fierce glare of sky and river around the bridge, others who stumble along and, leaning against the balustrade, pause to rest a bandaged foot; in numbers, too, mothers, each with a pale child asleep in her carrying scarf.

The paths that all this multitude have made, imprinting in the soil with wheels and hoofs and naked feet the record of their desire for the rich plain, come out of all the distances of the landscape south of the great river. Some there are that run along the shore down from the great waterfalls, where the ground is always slightly a-tremble with the

| |

| |

thud of the down-thundering floods and the air is damp and cool even at noon with the rising vapour; the tangled growth of the slopes and the thousands of purple, orange, and light red flower-disks of the lantana which shine out so gaily from amongst the dull rough leaves, are always delicately bedewed. These narrow paths glide sinuous and smooth like little playful snakes through the cool grass. Others come down from the steeps, past sudden juts of rock and precipitous slopes, where the slender young trees stand as if rearing; they dart into sight, grey out of green, and dive down again, like a doe leaping down the hills. Through the yellow-grey alang-alang grass that sucks up the sun's heat and holds it till the wilderness is as a seething pool, the narrow path creeps on like a tiger a-hunting; it is to be guessed at only by an all but imperceptible trembling of the tall white blossom plumes as some traveller passes along, feeling his way with arms upraised to protect his face from the knife-edged leaves. The mountain paths descend, steep and twisting, following the margin of the dark forest from the far-off heights, where, bluish-black with its own vapours, it clings to the mountain-side like some drooping thunder-cloud; along all the ever lessening, ever tenderer-tinted slopes, down to that last one, which, with its wealth of crowding tree-tops and sprouting thousand-hued undergrowth, glides softly down into the river. As deliberately as the heavily laden ponies driven along by the charcoal-burners, these paths proceed. And some there are that come down the hills where the slope is hewn out and banked up into terraced fields; as daintily and carefully as women planting rice they glide along the narrow dykes and over the little glittering falls of the irrigation water.

But the great road from the south coast, which, through the depths of the forest, moves broad and stately toward the bridge, advances like a prince riding at the head of his nobles.

As many and as varied as the ways are the desires that go out toward the bridge. And the bridge rises up to meet them all, broad to receive, strong to bear, like some good-natured giant who, bestriding the stream, his feet planted firmly upon the opposite sides of the foaming ravine, takes up a whole swarm of little people at once on his broad back and gently sets them down again where they wish to be, in the rich plain, which holds their satisfaction and their ever increasing desire.

Therefore, as it dominates the landscape from near and from far, so

| |

[pagina t.o. 62]

[p. t.o. 62] | |

The Bridge

| |

| |

the bridge dominates the daily life and daily thought of the mountain people. They have numberless proverbs concerning it; it stands for a symbol of many things. To the bridge they compare faithful friendship, help that forestalls supplicating need, patience that wearies not, however heavy the burden, far-sighted forethought that preserves from accident and adversity. In the pantoon-rhymes which they sing on festive evenings, they play a game of invention and imagination with it. The building of the bridge makes a division in their recollections, a hither and thither in time. ‘That is a matter of the days before the Bridge,’ they will say of what is past and gone, of old-time events. Parents tell young people how much sweeter life is now, in the times since the bridge, than it was before; how much happier the sons and daughters are than the fathers and the mothers were in the days of their youth. And they often add, ‘Blessed be the Builder of the Bridge, and blessed be his ancestors up to Adam the father of us all and Eve the mother of us all!’

In their talk of him the name that he inherited from his father is never heard; it is too harsh to their lips, accustomed to soft liquid sounds; nor do they give him his official title, as is their wont when speaking of those whom they know only as the bearers of the alien authority over them: ever the same the authority, a great and lasting thing; puny and fleeting the man who bears it. For him, as if he were one of themselves, they follow their own ancestral custom, which with the name plainly denotes the person, according to some quality of the body or of the soul; so that a child bears one name, but another name is borne by the grown man or woman, by which they are commended as the strong one, or the wise one, or the heart-rejoicing beauty. So they name him in praise of what he was to them: the Builder of the Bridge; or as often, too, they will say ‘Our Friend.’

Near the northern abutment of the bridge - where the low marshy ground, which becomes a river in every rainy season and remains a morass for many weeks in the season of change, slopes up toward the firm land and the populous high road - there stands an ancient banyan tree, a growth of a hundred stems, of a thousand swaying air roots, a forest in itself; the Builder used to take shelter in its shadow, as day by day he watched the progress of his work. From off the coupled barges that floated the pile-driver the men could see him as they drove in the

| |

| |

piles for the foundation of the central pier. And as, climbing up out of the quaking mud of the sunk shaft that was to form the foundation in the slippery unstable mire of the shore, the diver paused and drew breath, it was the Builder whom, first of all, he saw. From the first the wood-cutters in the mountain forest, and the lime-burners on the slope, and the mandoor of the Decauville railway, which runs down from the heights to the river with its heavily laden trucks, used to point out to each other the glittering white spot underneath the black-green hill of the banyan tree. The Chinaman who secretly bought away the cement out of the mixing troughs never returned after that dark night - it had seemed to him absolutely safe - when a white shape, issuing out of the darkness of the banyan, had moved toward his heavily laden barge.

In the mighty parent-stem of the multitudinous tree, a grey rock to the eye, rent, cloven, and hollowed out into deep cavities, the Builder had carved his name; half in meditative idleness, half perhaps in an earnest that understood the strange ways of thinking of the hill folk. As they appeared to the first who noticed these incomprehensible characters, so they seem to this day, to those who reverently contemplate them, a magic spell, powerful to ward off all evil from the bridge. They believe these tokens to contain the profound knowledge and the virtue of the Builder of the Bridge. They hang jessamine wreaths on the tree, little bags made of plaited strips of banana leaves in which sacrificial rice has been boiled, and ornaments of gilt and coloured paper, to secure a portion of this inexhaustible heritage of good luck. A man undertaking a long journey, a woman on the way to market, is not likely to pass by the banyan without some such offering. There are even tales of more than one mother who took a sick child thither and carried it home restored to health and smiling. Such power there is in the sign of the Builder of the Bridge!

Of him and of the building of the bridge, and of the daring deed by which he saved it from the devastating bandjir, at the time when, shortly before its completion into steadfast strength, it stood still frail, they tell each other tales which flourish like legends and are as melodious as songs. All through the mountain district, these tales wander to evening festivals full of radiance and gamelan music and lightly swaying dances; and pass over the rice-fields where girls with flowers in their hair gather the ears which the youths carry away in heavy sheaves; and

| |

| |

to the bathing place, cool with fresh-smelling water that leaps down in a cloud of spray; and to the shaded spot under the eaves, where the batik-worker sits before her richly colouring fabric, carefully held fast against the slight breeze that rocks the section of bamboo stem suspended above her head, the hive of the almost invisibly small noiseless bees which supply her with wax for her work.

A few only of these songs tell of how with his thought he wrought the wonder, that road that raises itself from the ground where roads lie, and, transparent against the light, passes through the air, over the foaming and swirling depth, a fixity to be trusted in. No such great miracle does this seem to them for the Westerner, whom they know to be a worker of wonders by his great knowledge. Tooan Allah created him thus, even as he created him white, and gave him power over dark-skinned people!

But innumerable and varied as the sun-flickerings on the flowing river are the stories and the songs of the deed which, with his naked body that shone with courage and strength, the Builder did for the salvation of the bridge, when the bandjir, the terrible, came down upon it. It delights them, even as the deeds of the heroes of ancient song. They celebrate it, even as in the long nights the dalang, half singing, half speaking before his lighted puppet show, or the tookang pantoon who hums in the dark to his instrument, celebrates the feats of arms of kings' sons in the heroic age, who, in their battling against Raksasas, monsters with the jaws of devouring beasts, and against fierce giants, were the chosen and ever victorious champions of the gods in their celestial palaces and the favoured of the fragrant and smiling goddesses.

This transfiguration of a compatriot provokes a certain irony in the Westerner, to whom this man does not seem, even for that heroic deed, in any way different from all others - grey with the workaday dust of the tedious labour that Westerners, the dominated of their own domination, have to toil at in the Eastern land; the labour that wrings out of earth, water, air, and fire, out of plant and beast and man of the sun-land, such sustenance for themselves as they shall need in their distant home, the day of return to which is always too far off. With a shrug of the shoulders they say that, thus glorified, no one would recognize the civil engineer who, when the line to the coast was laid, found means to win over the Government to his plan of building a bridge across the

| |

| |

Tjikidool in order to open up the hill-country - a project which, in reality, was made by others long before his time and urged again and again by successive Residents of the province, but which had to be postponed on account of the more stringent necessities of military policy and of punitive expeditions to outlying parts of the colony.

But the natives choose to represent their friend in this wise, in no other or lesser. This transfigured image of him is to them the true one - true according to the truth of the heart, which is to the truth of the senses as the sweet kernel of the grain of rice is to the hard and shining husk. Even as the chaff is blown out of the sieve of a woman winnowing the pounded rice in the wind, all outward seeming and circumstance is blown away out of the winnowing experience of time; but that which was in the heart has become the food of life, even as the rice-grain, and a beginning of things which, perpetually renewed, still endure. Therefore they sing unabashed their songs and rhymes and proverbs about the Builder of the Bridge, and, singing, are happy, and at times feel almost a desire to be such a man as the much-legended one was: strong and kind. Can this be yet, can this be? Terrific as the bandjir are many powers that forbid; but the smiling land of dreams lies open to fancies and longings. The far-away ancestors of this people, who found no living-space for their hearts' desire on the hard and dark and narrow earth, lifted their eyes to the skies; and, the rains and gales of the monsoon season having wrecked their hut, they rebuilt it of stars, so that for all time it shines on high as the Little Slanting House, the constellation which Westerners have named the Southern Cross. And they arose from the weary labour in the rice-field as the eternally unwearied Ploughman, Orion of the Westerners, who, in starry shape and girt with stars, steers a star-built plough that moves of its own strength through azure glebe and pool of cloud. Ever thus, they of the present day who find no living-space in the cold dark hard reality that now oppresses their hearts' desire of dominion over the powers of nature, of the happiness of a life in fraternity, raise to the heaven of poesy their vain longings; and in that glorious one who conquered the whirling flood and built a

road for the lonely dwellers in the hill forest toward the people of the spacious plain, they image forth their hoped-for self.

| |

| |

An hour came and a place was found for the meeting together of all these many imaginations, memories, and saws. It was in the night, a night of the season of change, between the months of the sun and the months of the rain; at the bridge. As is their wont, when there is danger of a sudden flood, a bandjir, coming down, the men of the river villages were on guard, to protect the bridge from driftwood. Thus there were many together there who at other times are far apart.

Old Hadji Moosa, who had been the friend of the Builder of the Bridge, was seated in the circle around the leaping flames of the watch-fire; and the village headman of Gandasoli was there, Sootan Arab, who, as a mandoor of the wood-cutters, had helped to build the bridge - a man from the south coast, from a village of pirates. And with the multitude, who paused in passing and sat down by the roadside, attracted out of the chilly darkness by the blaze of the watch-fire and, even more, by a faint tinkling of gamelan music arising by whiles, Soomarti from Kebonan Baroo had come, who was to go to Holland to be a student at a University, but whom his companions still called Moodjaddi, as in the time he herded his father's one buffalo and hid himself amongst the bushes to read the books with which the teacher at the Dutch school always kept him supplied.

There where the glow of the fire faded, but where the darkness which fell from the great banyan and its fringe of air-roots was not yet dense, twixt light and shade, the poet-musician, Si-Bagoos, was seated amongst his musicians and their manifold musical instruments.

And the daughter of the Radhèn Regent was there, Rookmini, of whom it was said that, in her father's stately house, she had refused to accept the homage due to an elder from younger sisters, and wished to be their equal in all things. And now she taught this new way of living to the girls who came to her school, in the great house that her father had given her. Daughters of the native nobility came there, and children from the village huts. She would have them all be as sisters and herself a mother's sister amongst them. She was not seated amongst the market folk by the road, but kept under the banyan where many wreaths of jessamine and champaka gave forth sweet fragrance; by the sign of the Builder of the Bridge she sat, in the midst of an ever growing circle of women and girls; the clipped air-roots of the banyan,

| |

| |

which hung down to within a few feet of the ground, formed a half transparent curtain between them and the men round the fire; dusky and transparent, it hung before the women like rain, seen against the evening glow; to the men it was, in the empurpling firelight, like steep rays of morning red playing over a dark drift of cloud.

As many people, grown men and women, youths and maidens and little children, as at other times can only be found at the passar or at some feast which a nobleman gives to an entire district, were gathered by the bridge and by the dark roadside on that night.

In the clouded heavens the moon drifted like a boat amongst grey billows, overwhelmed at one moment, emerging the next. In the shifting light the steep southern shore of the river, and the bridge, and glimpses of the distant plain with an expanse of sea seemingly sloping up toward the horizon all silvery with moonlight, shone out and again disappeared into darkness. The Tjikidool roared against the abutments of the bridge and around the central pile; the water voices joined in the tale that then was told, and that since has been repeated how often in how many places on how many days and nights! - a strange tale, a tale of great things and of smallest intermingled. The singing of Si-Bagoos was in it, and the teaching of Hadji Moosa, and the plaint of the old men who still remembered the sorrowful days of solitude, and the chattering story of the men who knew about the felling of the wood and the digging of the foundations and the building of the bridge, the thieving and receiving and the secret trafficking in building materials, and the squabbles between hill folk and people of the plains. As full of inventions it was as the sarong which a skilful batikker has painted with dragons, butterflies, and flowers, red, blue, and brown on a yellow ground. As diverse it was as the water of the river which, surging out of the darkness all heavy with drift, mingles in one wave the limpid waters of the mountain lake, cool with the light of the stars, and the refuse from the village ditch. A thing of the season of change was the river that night; a thing of the season of change was also the tale. And the bridge, dimly seen by glimpse of moon and flicker of flame, stood as a watcher over all, the deed perfected protecting the memory of the deed in its growth, and the hope of deeds to be accomplished in the days to come.

| |

| |

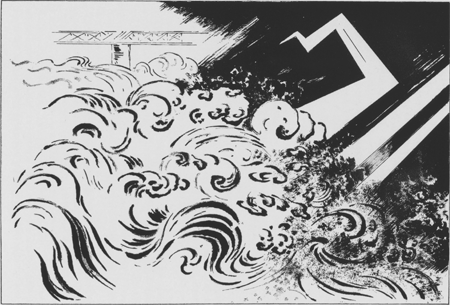

There had been a cloud-burst in the highlands that night. Now all the mountains rushed with rain; and the great river rose. Out of all its thousand springs on cloudy slopes and in ravines dark with damp wood; out of its mountain meres tranquilly clear, reflecting the sky only and the soaring eagle; out of the bubbling sources on the hillside, the springs, the rills, the brooks, the steep cascades of the ravine that scatter in a flying spray over the tops of the slender-stemmed wood striving up toward the sunshine out of depths of darkness; out of the pools, purple with water-hyacinths; out of the great lake, where the tall-stemmed lotos flowers, white and red, glimmer on the wind, a tremulous radiance seen from afar; out of the dull green marsh, misty with clouds of mosquitoes, hideously astir with the writhing of pale-bellied snakes, breathing fever over the shivering villages; out of the flooded terrace fields of the hill range and the rice-swamps of the plain; out of all its tens of thousands of gathering places, the water was flowing toward the Tjikidool.

It was raining in the highlands, raining. Over the cloud-swathed mountain-tops the air was all rain.

The zenith was a black well-spring, the clouds its waves. Out of it gushed, transparently dark, a fall of jetting streams; out of it in a cataract, standing steep between sky and mountain-top, sprang the Tjikidool. The river of rain beat down upon the glistening mountain-tops, blunting and dimming them as the ripple blunts and dims pebbles in the valley bed. The mountain forest stooped under it, like pliant water-growth under the wave, palely bending and dragging on its roots to follow the impetuous current. The underwood along the brink broke away and shot down the slope, that was changed into a brown cascade. The deep ravine had leapt up, a seething whirl. It tore at its walls; bushes, trees, earth, and rocks tottered and were precipitated into the sounding depth. The waterfalls by the Stone of the Sparrow-Hawks, where the torrent bursts forth from its black mountain gorge and leaps down into the space and splendour of the great plain, came down crashing with the weight of rolling masses of rock and hurtling trees dragged along with root and branch.

In the villages downstream the people sat watchful. More than one thought anxiously of his plantations on the slopes. The coffee had blossomed so profusely! The rice was sprouting so lustily! Alas! the

| |

| |

shrubs, surely, were lying broken and torn under the muddy gravel now; no doubt but the rice-field was floating downstream, glebe and stalk! And the husbandman once more cursed the nomads of the western hills who set the hillside on fire to sow their rice in the ashes - the reckless destroyers of the forest, which holds the slopes together with its twining roots and, catching the rain, gently filters it through its spread of leaves. And all the more angry he grew with the lighthearted young men, who had gone up into the hills as to a feast, a merry hunting party, following the sound of the rumbling landslip. They well knew that the bandjir, the fierce hunter, had slain numberless creatures of the forest, flinging them down hither and thither on foam-covered heaps of boulders, and they would bring away the quarry before the swarms of small beasts of prey came for them, and, in the evening, with his green shining eyes, the tiger.

As the evening red broke dully through a smoky brown of clouds, the river to the east of the Stone of the Sparrow-Hawks began to rise. Sluggish and turgid, the flood rose. In Tanah Abang, the first village downstream from the falls, the watchman stood at the gate, listening; and as he caught the signal for which he was waiting, sounding out above the thundering crash of the cataract, a long, deep, clear note, he seized the wooden hammer and with a swing of his arm struck it against the suspended hollow block. It rang again. Over the village, over the river, over the hills, the bandjir signal resounded, in answer toward the Falls, in warning toward the Lakes. The swinging hollow trunk, the tree-bell, a crier in the native villages, mightily he called, called to the other bells upstream and downstream, called all the villages along the river.

They heard it, one after another. And one after another repeated the tidings and the warning:

‘Be on your guard, be on your guard! The river is rising!’

It grew into a chorus. The villages on the hills joined in, and the villages of the plain. There were some calling here, there were others calling there; they called aloud through the darkness. On the river-shore, in the rice-fields, on the slopes and the hilltops, in the valleys, in the forest they called one another to come and watch by the bridge, that the bandjir, the ruining hill of waters and woods, might not, with its

| |

| |

ramming tree-trunks, destroy the piles and the abutments of the bridge.

The villages were calling through the night. The voice of each had a note of its own. The voices of the villages on the river were clear - the water carried them along in perfect purity. But the hamlets in the forest gave forth a muffled sound; the weight of mud-soft leafage heavy with damp lay upon the forest. The voices from the slopes and the heights were tenuous; they glided, tremulous and tense as the flight of the swooping swallow. And those in the narrow valleys mumbled indistinctly. And those of the plain rang out with a spacious sound. A listener with a fine ear might have discerned the lie and shape of the village-bearing land by the notes of these bells as plainly as if he had seen it spread out in the sunshine, so clearly it stood imaged in sound.

At first the bells had called all with the same call, uniformly, in one measure. But after a time there came a change; for each had now a message and an answer of its own to give.

Some called: ‘The river is rising, rising!’ and others: ‘The river is rising: guard the bridge!’ To this all together answered: ‘We are on our way, are on our way; we are on the way all together.’ And a few: ‘We are keeping watch!’

But suddenly - and then all the others were silent - a new voice resounded, the greatest of all, the deepest, in which there was the most of earnest and authority. That was the great bell by the bridge.

It called out over the nocturnal landscape: ‘Come, come ye all! Sons, come!’

In the dark houses the men rose. The women handed them as they went the kindled torch that was to light their way. On all sides then there began a flickering, and there, where the great bell-voice resounded, a great light shone up. As the sound of the bell was deeper and stronger than all other sounds, so this light was broader and brighter than all other lights. It shone out afar, red and full of scintillations as the red star which, in the constellation of the Ploughman, is the bleeding wound in his foot, stung by a small snake of the sawah. Steadfast it stood among the multitude of wandering lights, the one motionless, as steady as the star. They stood by one another, fraternally, the great bell and the great watch-fire, twin signs of the bridge.

| |

| |

Toward them moved all the little flickerings, the hastily swinging, swaying, waving ones.

As the calling bells revealed the villages, so the paths in the landscape were revealed by the moving lights - all the paths that lead toward the bridge, the upward paths out of the plain, the downward paths from the hills, the paths along the river upstream and downstream, the paths on the edge of the forest. As they glided onward they drew through the darkness the meshes of a net of roads, an immense net which a giant fisherman standing upon the bridge was hauling up out of the waters of the night. Ever more numerous and ever brighter strings and meshes of light he drew up to him, while all the time the great voice at the bridge continued calling: ‘Come, sons, come!’ And still the answering cry came back: ‘All our men are on the way!’ ‘We are drawing near!’ ‘We are making ready!’ The glittering net shrunk together, became a billowing circle of light around the great fire at the bridge, was burnt up in it.

The bells fell silent.

By this the women in the dark villages knew, and told the children, sitting upon the sleeping-mat wide-eyed and restless, that the watch was come together by the bridge. By the great fire far away father was sitting now, and he was watching for them, that the bandjir might do no harm to the bridge that they passed over every day when they went to school.

The men from the four villages that neighbour Gandasoli had the first turn, together with the men from Gandasoli. The village headman, Sootan Arab, who had been a mandoor of the wood-cutters at the building of the bridge, called them by name, each according to his place and duty, to the shores of the river, with hooks and loops to catch the driftwood and make it fast to the trees on the bank; or to the abutments and the centre of the bridge, to fend it off with long poles from the central pile and steer it under the arches so that it might float away to sea.

The tall, lean man, who, by his broad chest and shoulders, might be known for one who had rowed a prao on the sea from childhood, and who had a sea-face too, bold-featured and fierce-eyed, raised his ringing voice. Tones of as searching a resonance are heard on the islands along the coast of New Guinea, where the wild Alfoor folk wind Tri- | |

[pagina t.o. 72]

[p. t.o. 72] | |

New Guinea

| |

| |

ton horns calling one another from island to island, over hills and flickering sounds, with the peals of that magnificent trumpet.

Hadji Moosa, the old man who had been the friend of the Builder of the Bridge, sat close to the fire, his hands clasped round his knees and his wrinkled face raised to the warmth of the flames. It moved and changed strangely in the changing light. So deep in thought the old man sat that he never noticed the pealing voice of command, nor the faces of the multitude around the fire, nor those of the constant procession across the dark bridge; faces which in advancing became distinct for an instant in the radiance, then melted back into darkness while those succeeding them were lit up.

There were many people journeying to the plain, because of the great passar at Djalang Tiga, and of the dedication festival at the new sugar-mill that a Chinaman had built; and especially because of the expected arrival in the harbour of a ship bringing home pilgrims from Mecca. Dark and with a deep muttering like that of the river in the depth, the throng streamed by. And as in the river of waves, so in the river of humanity there were sudden eddies and whirls, when a group of pedestrians halted to ask or to bring tidings of the bandjir, and those advancing paused and those who had gone on turned back to listen. As the steadily rising river here and there scooped out a tiny bay in the shore where the on-hurrying waters eddied for a while and then became even, so the stream of travellers here and there along the side of the road deposited knots of people who prepared themselves to spend the night there. Amongst them there were many young folk who, from afar, had caught a glimpse of brass gamelan instruments on the edge of the flame-lit circle, and had called out to one another that surely the Dalang of Soombertingghi was resting there on his way to the consecration festival in the plains; Si-Bagoos it was, of a certainty! That was a decoy light indeed, that glimmer of waiting music! They came to it as crickets to the lamp of the cricket-catcher, shining out of a heap of stones at night.

Then in the dusk of the banyan, where the musicians were gathered, they became aware of indistinct female shapes. The women who had gone up with flower offerings to the sign of the Builder of the Bridge remained there. That was because of Rookmini, said one to the other.

Timid, but eager, the women approached the Radhèn's daughter

| |

| |

and took courage as, in answer to their murmured salutation, they heard her grave, gentle voice, that was like the deep crooning of the turtle-dove, the bringer of good luck. They seated themselves around Rookmini, in the darkness that fell from the banyan. As around the watch-fire the lighted circle of men grew, so around her the dim circle of women still grew. The fringe of clipped air-roots hung between them, transparently dark, interwoven with shifting gleams of firelight.

So gently as to be imperceptible save by the gradual increase of the fragrance drifting from the flower offerings at the foot of the tree, a waft of cooler air passed by, the first soft breath of night. And, as if borne along on that slight current, together with the scent of the roses and the jessamine, a soft music arose from the gamelan orchestra, so restful in its rhythm that listeners felt its ripple like the flowing of the blood in their veins.

The voice of Si-Bagoos then arose in half-singing speech. As upon placidly flowing water blossoms drift, fluttered down out of overhanging foliage, and a rosebud floats amongst them or a purple oleander flower that has dropped from the hair of a bathing girl, or a handful of jessamine out of the sacrificial basket laid on the wave by the next of kin of a new-born child, so on the gamelan music the words of the poet-musician drifted.

‘As the fragrance of the jessamine which women piously bring to Our Friend's resting place, whence he beheld the work of his thought growing, work begun and completed for our sakes, so in our hearts is the fragrance of gratitude toward him. As the gleam of the white champaka flower in the morning sun, when it shines forth from dense leafage, the thought of his deed is in our remembrance. How he built the bridge, a road over the impassable stream, how he saved the bridge, in the bandjir, striving against stream and forest, against the dark powers, even as Ardjoona strove against the Evil Giant - thereof we will sing and tell. Let us do honour, brothers, to the courage that sprang not from desire for power; nay, that had its source in brotherly love.’

He ceased. With a slight modulation the gamelan music glided over into another measure. And now it became the melody that sings a welcome to the guests at the beginning of a feast.

| |

| |

In complacent expectation of coming pleasure the multitude waited, the women in the dusk of the banyan, the men in the light of the flames, the throng of market folk in the darkness of the road. Those who a moment ago passed by without looking back, lingered, paused. By the roadside the groups became more numerous.

The melody of welcome ended. Like fireflies in the dark the last clear notes hung for a while in the air, tremblingly afloat; then they soared away into the distance. And after a pause of silence a new melody began, which was slow and solemn; it suited well with the darkness and the deep muttering of the river; it carried well the words of the singer.

‘As a traveller who out of the wild and perilous ravine has been led up by a wise guide to a safe place, where pleasant rest and coolness await him, a meal offered by a friendly hand with words of welcome; as from the heights attained the traveller looks back once more, plumbing the depths with his eyes, and with his heart the long wandering, the fatigue and the anxiety; then all the more does he rejoice in his friend's roof, greeting him with a kindly gleam - so will we, living happily in the present day, look back upon former times, the times that were before the building of the bridge; all the more shall we then rejoice in the time that is now.

‘Far off are the days and dark as the depth of the ravine; then the Forest King was sovereign over the people of the mountains, the Lord of the Great Solitude. Many were his sons, many his servants, his allies many and most mighty. The spirits served him that steal through the darkness and entice men over the edge of the ravine. Fever is his child, that turns over on mud and rotting leaves as on a sleeping mat. The great proud beasts served him: the tiger with the terrible eyes that flame through the night, the wild bull buffalo, between whose horns rides death, the rhinoceros, the dreaded hunter of those who hunt him, the herd of wild pigs that root up the fruitful plantation, the gliding snake swollen with venom. The mountain was his ally, and the wind that comes from the mountain; the clouds that are the floating springs and rivers of the air. The tall grass of the wilderness, the alang-alang, was his army; ten thousand times ten thousand is their number, whose banners, streaming white on the wind, become new thousands upon thousands, conquerors of all empty places. Food for men grows there no more.

| |

| |

‘How could the people of the mountains strive against the Forest King, the dread prince of spirits and his innumerable hosts? How could they escape from his power by flight? The Tjikidool who was his ally watched at the kraton gate. Impassable was the stream. From afar too he deterred those who would approach from the plain. He terrified the horseman and the horse; the heart of the man was filled with fear, the horse reared white-eyed. He terrified the cart driver and the bullocks before the cart. In vain the driver muttered incantations; like the stone bull which stands in the great temple of Boro Buddhur, the bullocks stood motionless. Of good things none, neither help nor friendship nor joy, did the inexorable river allow to come to the people of the mountains. But for evils and disaster it was a ready road. It carried hunger to them. It carried to the mountains the army of rats when they fled from pursuit in the plain; it carried to them who owned but little the devourers of all; the plague it carried to them, and death.’

A movement had passed through the multitude of listeners as the poet-musician began to sing of the year when the great plague of rats came. They looked away from him to where amongst the throng of dark heads a few glimmered white. The very oldest only knew of those far-off days. Would they not speak? For although no one will ever interrupt the dalang when he lends his voice to the gaudy wayang puppets moving before the white screen to tell of the high exploits and adventures of gods and godlike heroes, or the tookang pantoon, who, alone in the dark with his music, chants the long verses of a fairy tale, this was no fairy tale nor legend of strife of gods; it was of events still within the memory of men that Si-Bagoos thus sang to the melancholy music of the gamelan. And it seemed as if Si-Bagoos, too, were waiting for an answering song to his song of the great calamity, for when the words of the coming of the year of horror had died away he sat, as if expectant, in silence, and like the others he had turned his face to where the white heads glimmered amongst the thickly clustered black ones.

As in the wood where bats hang to the branches in their day-sleep, large and heavy and motionless, hardly resembling living creatures, but rather like some misshapen fruit on the leafless tree; as in the wood of the bats the report of a hunter's rifle startles all these sleepers, so that they unfold their filmy wings and sail aloft with a plaintive cry,

| |

| |

and the air is full of darkness and wailing, there where but now all was blue sky and the soft rustling of leaves - so at the singer's words of the year of distress, the memories awoke that slept in ancient hearts, and from those who had sat silent they rose up moaning.

A slow, feeble voice began. ‘I it was, I, who saw the sign of the disaster; I who was a young boy then. I was helping my father at fishing. In the evening we had set out our net in the river; I went forth before dawn to draw it up. Eh! how heavy it was when I drew it up on to the shore! Such a catch, I thought, we never had yet! I shook out the net on the grass. O children! while I am telling of it I feel my hair stand on end as it did then, when my eyes beheld the horrible sight! no fish, no fish, but a hideous heap of dead rats! Crushed together and hanging on to one another by teeth and claws, they stuck fast in the net, most loathsome to see. I stood as if turned to stone. When the bathers came to the river, they saw the devourers in the net - hunger caught in the stead of food. Oh, what lamenting then arose!’

A second plaintive voice began: ‘I had a rice-field by the river; I saw it wither. Withered were all the fields upon the slopes, withered the fields around the village; sere upon the ground lay the stalks, sere the unripe ears. The ground moved and swarmed, invisible life stirred in it, life that destroyed life - life that was death.’

A woman's voice arose: ‘Our mothers spoke to us: “My daughters! the time is near when the village headman sends the messengers to the households with glad tidings, summoning them to come up for the gathering of the harvest; and the girls carefully arrange their smoothly folded raiment, and place a flower in their hair next to the wooden harvesting knife which is their ornament on this day, thinking of the young men who will come to meet them in the field, thinking of feasts and betrothals and happy weddings. The time will come, but not the message. No lovers are waiting amongst the harvest. The rats have devoured your wedding feast, my daughters!”’

And a second spoke: ‘My husband went to his father, begging for the loan of rice. His father asked: “How shall he lend who is in want himself?” I went to my mother's brother. My mother's brother spake: “We have sought for the last grains in the dust of the corners of the rice barn; we have scraped the floor.” Then my husband went into the forest to seek for roots. Ah! what anxious days, how many anxious days, I

| |

| |

waited for him! My little child wailed in my lap; no milk was in my breasts to still its hunger. It wanted to drink; it bit the nipple so that blood came instead of milk. And I wept, but not for the pain in my breasts; I wept for my child's hunger. I wept, but not because of my loneliness - because of the wandering of my husband in the forest it was I wept. Where, I thought, is he, where is my husband now? Perhaps he has fallen into the ravine, and no one hears him moaning. Perhaps a wild boar has attacked him, or the bull buffalo that keeps watch over his herd has rushed upon him as he entered the clearing in the forest. Perhaps the tiger has carried him away, the mother tigress that carried away Djodjo, dragging him out of a circle of men as he was sitting in his own house, in the village that is all surrounded by the alang-alang. I was as a corpse with fear till he came back. Little it was he brought who had searched so long; but little! Ah! my little child, it died!’ She ceased on a sob. Tears stole slowly down her wrinkled cheeks.

A voice that was as a sigh rose out of the multitude by the roadside. ‘Mother-of-Sidin! how many a mother wept then even as thou didst weep, for her beloved child! Oh, how many children died in the hill villages then! Their little bodies were so thin, their little faces were like the faces of old men.’

A dull man's voice spoke. ‘First the little children died and the old people, those who had but little strength as yet and those who had strength no more. Then the men and the women died, those who were full of strength. The mice had eaten up their strength as it stood afield. As the mice devoured the field, so hunger devoured the men and women, eating from within outward. It ate their bowels and their flesh, it ate itself out through their skin. They were nothing but hunger. And then came the sickness!’

He was silent for a long time and then began again: ‘A great evil the hunger had been! a greater evil was the sickness that came after it. Of no avail was the art of the dookoon; all the lore that he gathered out of magic books was of no avail. Did we not do in all things as he commanded? We offered up all the sacrifices, even those that were the most difficult to accomplish, even the most costly; we performed all the sacred acts, we pronounced all the incantations. We tied bunches of prickly aloe leaves to the posts of the village gate in order that the sick- | |

| |

ness should fear to enter. Every evening before sundown we set down a bowl of yellow rice and a bowl of water and spoke the words of invitation, that the sickness might eat and drink and, being refreshed, pass on, well disposed toward our village, sparing us. But for all that, it came in! All the houses of our village it entered and slew the father and the mother and the ancient grandparents, all the children, the grown up, and the little ones; only a few remained to bury the dead. Hastily they buried them; they did not wind them in a white winding-sheet, they did not recite the prayers of the dead. With averted faces, fearing that death would come forth from the dead, they threw a handful of earth upon them. In the night the hungry dogs came. They fought by the new-made graves. No one drove them away from the thing which they tore from one another and devoured.’

The old and faltering voice spoke in dread. ‘Not all were dead that the buriers buried. A man came into our village, lean and naked; he staggered in his walk, swaying as a glagah stalk sways in the wind. He made gestures to beg for water, and drank, lying where he had fallen down. Not for many hours did he speak: then he said he had been buried, seeming dead. And he showed the bleeding bites of the dogs in his flesh.’

When the voice ceased it was very still. The soft rustling made by the night wind in the dense mass of the hanging banyan foliage became audible; the river was grinding against the abutments and the great pile of the bridge. A cloud that had long obscured the moon drifted away, and the misty light suffused the sky and the landscape; between dark masses of driftwood the river glimmered uncertainly, and on the steep southern slope the wood, crowding upward in billowy masses, stood in a dim silvery shimmer. Under that transparent surface lustre impenetrable darkness lay sunk in clefts and hollows, a cruel mystery.

But the gentle thrumming that all the while had softly continued grew gradually louder and clearer, although it still was very gentle. And now a girl's voice floated out upon it, and another followed; tender and timid were they both.

‘The mother weeps on the grave of her beloved child, bringing food offerings on the days consecrated to the memory of the dead; yet she smiles when at her return the other children run to meet her; for the sake of the lost one she loves the living all the more tenderly. The pen- | |

| |

sive one sighs, remembering the woe of bygone days; yet he rejoices in the gladness of the present day; for the sake of what is lost he prizes what is gained the more dearly.’

The soft voices of consolation sank again into silence. And on a lighter melody Si-Bagoos raised his voice anew, celebrating the coming of the builder of roads to the hill country.

‘As in the heavens the sun rises over the sea, throwing a golden road to the land, golden over all the waves, thus in the plain arose the Builder of the Bridge, the builder of many roads, the man strong in the strength of knowledge, born in a land across the sea; a shining road he made to the mountains, shining across all the fields. From the sea unto the Tjikidool a road of white beams shone out before his feet. No terror had the river for him! As the heavenly hero looked upon the giant, so he looked upon the Tjikidool, with the look of the conqueror.’

A call to battle rang out in the music that bore this song; gallantly it echoed through the night. Every face was raised. Sootan Arab, he of the storm-bird countenance, sat breathing deeply. Presently he joined in the song, humming, with a sound as of a gong that is covered up by a subduing hand. Hadji Moosa looked up out of a long reverie. There was great beauty in his thin, still face as he lifted it out of the glow of the flames; a tender pride lit up its sadness as the cheerful gleam of the fire lit up the dead leaves, dry and brittle, that dully strewed the ground. His voice trembled with the joy of love as he began to sing the praises of his friend.

‘As the rising sun is full of comfort and the dispenser of joy, causing the buds to bloom on bushes chilled by the dews of night, causing hearts to rejoice within sad ones, dimmed by the tears of the night, even thus Our Friend was a comforter and generous in the dispensing of joy. Being strong in the strength of knowledge, he gave of his strength to the weak, the ignorant. The building of a road over the Tjikidool, the impassable stream, a road for the people of the mountains, a fixity well to be trusted, this was the thing in his heart; no other. Not the winning of honour, nor the winning of power, nor the winning of riches. No overlord would he be, who was the strongest of all, but a helper of the weak. Well do I know - I, whom he called friend. Difference of white skin and dark skin, difference between the race that rules and the race that obeys, were as nothing to him.

| |

| |

‘When he saw that a humble man took thought and could not understand, he would say: ‘Come to me in my own house, in the evening, when the work of the day is done; I will make it plain to thee.’ Where the railway runs through the sugar-cane fields of Kalimas, there stood his dwelling. Many knew the way thereto! Sitting in the darkness, I looked forth toward his window; the light shone out; I knew, now my friend is waiting for me! I went as if the light were a hand that held my hand. He sat in the midst of many books. On the walls of the room were maps; thereon the land was drawn and the river, not as they are seen by the eye, but according to their true shape, which is discerned only by thought. Of what nature is the soil of the plain and the stone of the mountain, of what nature is the motion and the strength of the water, what are the places from which the water flows, all this was to be seen on these maps. And Our Friend explained it to us so that all of us understood, and understood too why it was that he who would build a bridge over the Tjikidool must know all these things. For even then that was his desire; he, Our Friend, wished it before yet any one else wished it. While no one thought of us, he thought of us - he of the gentle heart, the truly kind one!

‘From the window of his room, that was to the south, he looked upon the river, upon the place where the ford was in the dry season; in the time of change how often the people sat there waiting! waiting all night if haply the river would have fallen so far in the morning that, wading in up to the lips, a man might venture to cross. But often the river fell not - nay, it rose - and fell not the following day either, and those who had waited long in vain threw down their burden in anger and despair and returned home, poorer than when they started, and their feet became heavy as they thought of their children who would run to meet them, and of their wife, and of her eyes when she should look at the shoulders lacking a load and at the girdle lacking money. Ah! how many watch-fires burned in vain by the river in those days! He saw them when he looked up from his work. He well knew those fires were not the fires of a man from Hootan Roosa, or a man from Soombertingghi, or from Bookit Berdoori; no, all the people of the mountains it was, that sat there waiting on the bank of the impassable river. For a long while he would gaze in silence. The fires of the waiting ones in the night, they burned into his heart.’

| |

| |

The voice of the old man broke. For a while only the sound of the river was heard, growing ever louder as the current scoured with ever increasing violence against the great pile of the bridge. Some one threw an armful of twigs upon the fire; a tall flame leapt up, illumining a circle of grave faces, all turned toward the Hadji. Out of the semi-darkness of the throng by the roadside Soomarti's eyes shone; they were bent on Hadji Moosa as the eyes of a starving man are bent on food.

The friend of the Builder of the Bridge began anew: ‘I had told him I was a man from the mountains; he asked me how we lived there. But seldom, verily, will a man of this country give true answer to a Hollander asking him. Will not the humble one think that the mighty one asks in order to become the mightier by knowledge, and still humbler and poorer will he himself become thereby? Therefore he says not the things that are, but he seeks for words that will hide the truth under an appearance pleasing to the mighty one. But him, Our Friend, I knew to be our true friend; his question was a brother's question asking his brother that he may help him. As a brother's answer, therefore, was my answer, upright, truthful. I showed him the joy of our life and the sorrow. We spake, he and I, from heart to heart.

‘Woe is me! How poor am I become who was so rich then! Never more shall I sit with my friend, the truly good, the kind of heart, whose laugh was as the sunshine! I am old. He is far from here. I have given up waiting - I, who am an old man.’

His white head sank down; he sat all drooping. The glow had left his face; it was dim and hollow in the light of the flames. Tears that had been slow in coming and that were now no longer to be restrained, trickled down his wrinkled face.

Si-Bagoos turned and lightly touched the gamelan instrument; it sounded softly. And out of the dusk of the banyan there came a soft singing. ‘When the fragrant akar-wangi plant dies its root is still fragrant; we lay it among silken garments; all the garments grow fragrant. When days of joy are past, the remembrance is still joy. We treasure it in our thoughts; all our thoughts turn to thoughts of joy.’ The voice that sang the words of resignation was so young, never from the same heart could the voice and the words come; but it sounded sweetly, nevertheless.

| |

| |

And full of the consolation of sweet music was the melody which, out of Si-Bagoos' fingers that had so lightly touched the bronze, the gamelan player now took over and continued to a gliding, tripping rhythm. Hadji Moosa had raised his head again; he sat still, looking into the flames as if he were gazing at a fair vision. The flame was before him as a purple veil lightly wafted aside from the entrance of a temple; in the contemplation of the innermost shrine the self-forgetting gaze loses itself. He saw not how many eyes were bent upon him - neither Soomarti's face nor Rookmini's, as she gazed at him from under the banyan.

‘One thing was in the heart of Our Friend, one single thing. Even as the flame of this watch-fire outshines the torches of the watchers, even as it consumes the wood thrown upon it, the green with the dry; so this one desire outshone all other desires, so this one thought consumed every other thought in his heart: to build roads through the wilderness, that neither jungle nor mountain nor deep ravine nor river in bandjir should any longer part men from men, that there should be no more loneliness and desolation anywhere, but everywhere community and brotherhood. He showed us of what nature is the work of building bridges; how noble a work! And it has been honoured as noble by the wise from the farthest times.

‘This it was that Our Friend told us; I repeat his words, of which I have not forgotten one:

‘In the times as far off as the times when the Prince of the Wise lived, King Solomon, the lands across the sea, where now the great cities are and the palaces of mighty rulers, were wilderness and forest and marsh. And men lived there as in the wilderness of this our own land men live, and even more unhappily still, because over there but little fruitfulness is in the earth and but little sunshine in the sky. The world is poor there! There are many dark months in the year there, when all plants die; and in those ancient times many men and women also died; of cold they died, and of hunger, and in the struggle with strong and cruel wild beasts.

‘One people, however, there was, which lived in a different way. Earlier than all the others this people had gained knowledge concerning the earth and trees and plants and beasts, so that it ploughed and sowed and won plenteous fruit, and dwelt in well-built houses and wore

| |

| |

garments cool in the sunny months and warm in the dark time. This people did not wander, nor did it stray in the wilderness, but it built cities to dwell in, and from city to city there ran a straight road, and over every broad river there was a bridge, so that each town received what it needed from other towns that had it; and not only was it market ware that they carried and exchanged, passing along their roads and over the great bridges that made a road where first a swirling river had been - nay, but knowledge also. Thus ever greater became their knowledge; and they, being grown strong by knowledge, became the mightiest in the world, and rulers over all other peoples. In the conquered lands, where men still lived as the beasts live, they then did as they had done in their own land: they built roads and bridges, that are standing to this day, at this hour while we are speaking of them. The armies of this mighty people which held all the other peoples in bondage passed over the roads and bridges; but with them went knowledge. The armies could not prevent that! Those who were strong by knowledge could not hinder the weak, who were weak through want of knowledge, from gaining the knowledge that they themselves had brought with them over their roads and great bridges. The weak ones grew strong by it! They grew so strong that they drove out the alien rulers, and again became masters of their own land. Now they lived once more according to their own will. But this was no longer as it had been before the strangers came, the builders of bridges, for knowledge had wrought a change in them. After a long time they themselves became conquerors of peoples and lands, and in the conquered lands they built roads and bridges, over which their mighty armies passed to keep those peoples in bondage. But again with them went knowledge! Knowledge went over roads and bridges to peoples where as yet no knowledge was. Where formerly the forest had been their lord, and

the strong beasts, the tiger, the wild buffalo, and the rhinoceros, the herds of wild swine, where the alang-alang had been their lord and the impassable river, there came knowledge, by which man himself grows to be the lord!

‘And now in all those lands men are changing. They wish no longer to live as their forefathers lived, in dread of the many things stronger than man, for now they themselves are becoming the strongest! How it is they wish to live - that they do not as yet well know. The conquerors, who built the ways for knowledge, do not live happily in their own

| |

| |

lands. These people will not live as the conquerors live. How then? How then? They will know when they shall have gained yet more knowledge; when yet more men can come together, each giving the knowledge that he has gained in exchange for other knowledge that others have gained. Therefore they must make roads through the wilderness; that men may come to men, therefore they must build a bridge over the impassable river, that knowledge may pass over it, and men at last learn how they may live in true happiness, all together as brothers live.’

An exultant note had come into the old Hadji's voice, his face shone, it was young with joy and hope. And from all sides other faces shone toward his, most of these very young, half shy as yet, with a smile that was only in the eyes, a light as yet but dubiously dawning. It had grown very still, with a stillness that was not disturbed by the sound of the rushing river. The hill forest showed misty in the pale moonbeams; the clouds, downily grey, lay like brooding wings soft and motionless on the air; the sprouting of all the new life which the rain had begotten could be felt as a hidden sweetness in the breathing warmth.

The dalang, who had taken the swathed hammers out of the gamelan player's hands, gently touched the bronze. And a melody began such as no one had ever heard as yet. The listeners thought, wondering: ‘What is this melody that Si-Bagoos is playing? How beautiful! How most beautiful!’ A strong, calm rhythm was in the music, as of a great multitude marching together in happy concord. Many voices were in it of men and women - voices as of such as are seeking and calling, and voices as of such as have found and answer; a singing of youths and maidens, frolicsome between children's play and men's work; the laughter of many little ones and the call of watchful mothers. But words there were none to this music.

Soomarti, who out of the darkness had come ever closer to the music and the light of the fire, murmured, speaking to himself: ‘How then must we live? How then?’ He did not think that any one heard; the words rose to his lips of their own will. But the dalang understood, and looked at him across the music, and shook his head gravely. Every one who saw discerned his meaning: ‘The words that say this, the words for this music, are not as yet.’

| |

| |

The elders sat pensive, but the young had shining faces; they were all a-throb, as, in the foliage overhead, the young birds which the dawn-like light of the watch-fire had waked. They sat on the edge of the nest looking into the glow, the tiny creatures; they were full of light, and their short downy wings were set quivering with a desire to fly; even thus, stirred with a great longing, these boys and girls sat tremulous. From where she was seated amongst the women, whispering in the protective darkness of the banyan, Rookmini watched them, smiling, happy.

Then the music ceased its song, and became low and subdued, waiting for a voice which it might carry; Hadji Moosa began again: ‘Many are the rhymes sung of the bridge, many and beautiful! But one rhyme has not yet sounded. Ah! Would it were made to-night! Would that pantoon-singers in couplets of rhymes that answer one another sang the song of the Beginning of the Bridge! Listen, grandchildren! Hear what the beginning was!

‘The command came from the Great Lord in Buitenzorg: Let a bridge be built over the Tjikidool! And the Radhèn Regents and the Wedanas and the Headmen and all those who are in authority gave orders to the people, saying: ‘Go ye and build!’ But this was not the beginning of the Bridge.

‘Wise men examined the nature of the river; they made an image of it, a true likeness. Travelling through the mountain districts, they investigated and enquired of many men, they discovered the sources, they measured the rain, they tried the soil; but this was not the beginning of the Bridge, not this either.

‘Our Friend saw how we lived. He saw the fires of the watchers in the night. His heart grew hot within him because of our need. This was the beginning of the Bridge!’

For a time there was silence after he had finished speaking. Then there came a voice out of the shadow of the banyan - not the young light one that had sung first; much fuller this one sounded, and at the same time softer. It sang words new-found, words just unfolding, like the sedap-malem flower, that unfolds in the night. The subdued melody which the musician played well suited the grave and gentle voice.

| |

| |

‘In secret is the beginning of the rice plant, in the dark grain, secret. In secret is the beginning of the bird, within the dark egg, secret.’

And, answering, a voice came out of the darkling multitude by the roadside; a youth's ringing voice it was: ‘In secret is the beginning of man, within the dark mother, secret. In secret is the beginning of the deed, within the dark heart, secret.’

The scale of sounds ascended in well-defined intervals, harmoniously: first Hadji Moosa's deep voice; then Rookmini's softly clear voice; then the youth's ringing voice. It had to come, that voice; it could not but come! The listeners were well pleased to hear that last high note.

But yet when they saw who it was that sang, they said, in some surprise: ‘Eh! it is Soomarti! It is Moodjaddi from Kebonan Baroo who sings in answer to Rookmini! Bold is he indeed that he should dare to speak - a boy amongst so many older persons!’

A sound of voices approached, and the light of torches. The watchers whose turn was over sat down again by the fire. They said that the river still rose and a great deal of wood still came floating down, but it was only shrubs and saplings, slight-rooted growth, of small hold upon the soil - no longer tall trees such as there came last year; nothing that threatened danger to the bridge.

The watchers whose turn now began rose to go to the river banks and to the middle of the bridge. And a tall man, to whom one of those returned from the river had handed his torch, turned in going and stood for a moment, shining, as he said that verily the day was a day of good luck, upon which the Builder of the Bridge had begun the planting of a wood on Goonoong Hitam. A good defence it proved from the violence of the rain upon the slopes! No more rice-fields would be destroyed of the many that had been planted since at the foot, and no more houses would be washed down the slopes as had happened so often before. He went: the flame and the smoke of his torch were as a banner over his head.

The gamelan music began again; merry was the melody. It sounded like an answer, a joyous ‘ay,’ a calm glad assurance concerning many happy things.

| |

| |

Sootan Arab raised his kindling eagle-face; that sonorous voice of his, that was like a call from a Triton horn, broke through the soft music.

‘A captain for courageous men was the Builder of the Bridge, a leader whom it was good to follow! My comrades and I, men of the south coast, who never follow any man, we followed him, and never rued it. He was like to no other, Hollander or Malay.

‘When we came back from our last expedition, then it was that we heard of him. Brothers, what a loss it was, that last journey to Timor for horses! - too unbearable altogether a loss. Four of the horses fell overboard in the fight with the Arab horse-dealer and his men. And we were hardly under sail with the others, when we saw the smoke of a revenue cutter. Even if the wind is favourable, how shall a man escape with sails and oars from a fire-ship? I said: ‘Brothers, better to be safe with a few horses than to be caught with many!’ Six horses we took into our prao; the prao of the Arab, with the others, we cast adrift. We also thought, perhaps the Hollanders will pursue the horse prao, and while they are busy with the horses we shall escape. There was a favourable wind, we rowed with all our might, we were close to the cliffs. Brothers, a little only, a little was wanting, and we should be safe. Then the revenue cutter overtook us! How shall a man escape from a fire-ship if he have only oars and a sail?

‘A bullet struck the water in front of our prao. We leapt overboard. They did not find us on the islands, however long they searched. We had reached the mainland, when we still saw their steam-launch darting hither and thither amongst the reefs.

‘And we saw our horses on the cutter's deck, all of them! All! Both those we had left in the Arab's prao and those that we had kept with us to the last - all the twenty of them! Ah! the loss, the all too unbearable loss! All in vain, all the trouble and the fighting and the rowing; all for nothing! A fool was the dookoon who offered up the sacrifice before we sailed. We said to one another: “Is this a life worth living, brothers? Better were it verily to be a coolie, a man who works with his hands, and does as he is hidden, a slave!” We heard of the building of the bridge, we saw the village of the coolies by the river, a big village, a very big village! The smoke of the noon fires was as a cloud in the sunshine. We had seen it at first on the skirt of the plain, not far from the

| |

[pagina t.o. 88]

[p. t.o. 88] | |

The Isle of Pirates

| |

| |

trading city on the coast. Then we had seen it in the midst of the plain, amongst the cane-fields and the sugar-mills. Now we saw it by the river: a travelling village, a village like a bullock-cart that goes where the driver drives it! And the iron road shone behind it; the fire cars were riding along it. We entered the village; it was full of food! No one gave us any. The people said: “Work! We also work.” We were terribly hungry; we thought, “It is even so!” We said, “We will work!” The mandoor accepted us, for some of the workmen, woodcutters, had just run away, so that they were in need of men. The Builder of the Bridge came and looked at us; he said, “It is well!” And we looked at him, and to one another we also said, “It is well!” He was a captain for men like us; that we knew, seeing him. Koowat and Si-Badil and I, we went into the hills to fell wood. That was work for men. The others had run away out of fear. They were afraid of the people of Bookit Berdoori, who had hit the mandoor over the head with a hatchet, after they had long been lying in wait for him.’

From the multitude by the roadside there came a feeble hoarse voice, like the crackling of dry leaves that break under foot.

‘Builders of bridges have need of a human head to lay under the masonry, so as to make the bridge strong to withstand the river and strong to bear burdens. The enmity against the mandoor of the woodcutters was because of this. Mothers dared not let their child outside the village gate; nay, they would not let it out of their sight, as long as the builders of the bridge were in the hills.

‘And because of the sacred tree was the enmity; because of the Rasamala on the burial ground of Hootan Roosah. The wood-cutters, men without shame, men from another district, had felled trees there. No one from our district would have damaged the forest of the Rasamala. Every grown man - ay, every child - knew what great misfortune that would bring on the people. And even they who were strangers might have known. Easy it was to see that the Rasamala was not a tree as other trees are - that it was the abode of a spirit. A mountain on the top of a mountain it stood; it was as a forest in the midst of the forest. Its base was as a rock. Five men holding each other by the hand could not encompass the trunk. The first bough was a hundred feet above the ground, and the crown a hundred feet above the first bough. The sea- | |

| |

eagle that came flying from the south coast alighted upon it; thence he surveyed all the land down to where the surf is white upon the northern beach. Even the men of the south coast, who gather swallows' nests from the steep of the rocks, durst not have climbed into the Rasamala for the bees' nests hanging in it. They well knew that death would have seized them before they could seize the honey!’

A second voice fell in, which also had the woodland ring. ‘It is said in Goonoong Hitam that there was a big village there once, before the Year of the Rats. Kasiman from Goonoong Hitam came to the wood of the Rasamala once, having lost his way. It was just after the great bandjir and the landslip which had filled up the ravine at the foot of the hill. Great clefts were in the slopes; many trees lay uprooted in the wood of the Rasamala. And in a cleft between the torn-up roots Kasiman saw something white. He thought, “Whatever may that white thing be, that white thing down there in the black earth?” He went, treading cautiously, to the edge of the chasm. Then he saw skeletons - many skeletons, as in the burial ground of a big village. Some lay prone with knees drawn up, and some on the side, all twisted. The roots of the trees had grown through them; a black wicker-work twisted among the white ribs. Then Kasiman knew that it was here that so many burials had been in the year of the great sickness, and those who had been buried alive had not been able to escape, being very weak and struggling against earth too heavy upon them.’

The hoarse feeble voice began again: ‘A forest of spirits was the wood of the Rasamala. Misfortune must come of it, if trees were felled there - great misfortune to all the hill country!’ The anxious tones ended in a cry like the croak of the raven.

And suddenly there was an echo on all sides. The night was pierced with the outcry of angry frightened voices, sharp as the sharp grass of the wilderness, that wounds the wanderer's breast and face and upraised hands and pierces the soles of his feet with its splintery broken stalks. Names of evil spirits were muttered. An angry voice cried: ‘A great misfortune came to the bridge because of this! The fever came of which so many died, and the cracks in the masonry of the sunk shafts, and the washing away of the foundations after the auxiliary bridge was put up. Eh! and did not the Rasamala himself come in the bandjir, driving against the bridge?’

| |

| |

A woman's voice screamed shrilly: ‘The women of Goonoong Hitam did well to guard their children from the mandoor of the bridge-builders, a lurker in hidden places, a man-hunter! But the spirits took for themselves the sacrifice which the builders would not offer up to them! When the men blew up the rock for the foundation of the bridge on the southern bank, a fragment of rock, flying through the air, tore off the mandoor's head. Then only did the building of the bridge prosper.’